I've republished this text by Sharon Crozier-De Rosa from "The Dialog" below a Artistic Commons license.

Sharon Crozier-De Rosa, College of Wollongong

In Western nations, feminist historical past is mostly packaged as a narrative of “waves”. The so-called first wave lasted from the mid-Nineteenth century to 1920. The second wave spanned the Nineteen Sixties to the early Eighties. The third wave started within the mid-Nineties and lasted till the 2010s. Lastly, some say we’re experiencing a fourth wave, which started within the mid-2010s and continues now.

The primary particular person to make use of “waves” was journalist Martha Weinman Lear, in her 1968 New York Instances article, The Second Feminist Wave, demonstrating that the ladies’s liberation motion was one other “new chapter in a grand historical past of ladies preventing collectively for his or her rights”. She was responding to anti-feminists’ framing of the motion as a “weird historic aberration”.

Some feminists criticise the usefulness of the metaphor. The place do feminists who preceded the primary wave sit? As an example, Center Ages feminist author Christine de Pizan, or thinker Mary Wollstonecraft, writer of A Vindication of the Rights of Girl (1792).

Does the metaphor of a single wave overshadow the complicated number of feminist issues and calls for? And does this language exclude the non-West, for whom the “waves” story is meaningless?

Regardless of these issues, numerous feminists proceed to make use of “waves” to clarify their place in relation to earlier generations.

The primary wave: from 1848

The primary wave of feminism refers back to the marketing campaign for the vote. It started in the USA in 1848 with the Seneca Falls Conference, the place 300 gathered to debate Elizabeth Cady Stanton’s Declaration of Sentiments, outlining girls’s inferior standing and demanding suffrage – or, the best to vote.

It continued over a decade later, in 1866, in Britain, with the presentation of a suffrage petition to parliament.

This wave led to 1920, when girls had been granted the best to vote within the US. (Restricted girls’s suffrage had been launched in Britain two years earlier, in 1918.) First-wave activists believed as soon as the vote had been received, girls may use its energy to enact different much-needed reforms, associated to property possession, training, employment and extra.

White leaders dominated the motion. They included longtime president of the the Worldwide Girl Suffrage Alliance Carrie Chapman Catt within the US, chief of the militant Ladies’s Social and Political Union Emmeline Pankhurst within the UK, and Catherine Helen Spence and Vida Goldstein in Australia.

This has tended to obscure the histories of non-white feminists like evangelist and social reformer Sojourner Reality and journalist, activist and researcher Ida B. Wells, who had been preventing on a number of fronts – together with anti-slavery and anti-lynching – in addition to feminism.

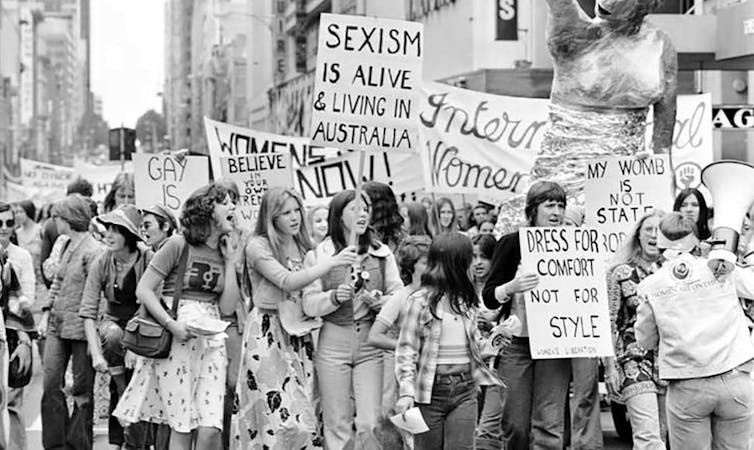

The second wave: from 1963

The second wave coincided with the publication of US feminist Betty Friedan’s The Female Mystique in 1963. Friedan’s “highly effective treatise” raised important curiosity in points that got here to outline the ladies’s liberation motion till the early Eighties, like office equality, contraception and abortion, and ladies’s training.

Ladies got here collectively in “consciousness-raising” teams to share their particular person experiences of oppression. These discussions knowledgeable and motivated public agitation for gender equality and social change. Sexuality and gender-based violence had been different outstanding second-wave issues.

Australian feminist Germaine Greer wrote The Feminine Eunuch, revealed in 1970, which urged girls to “problem the ties binding them to gender inequality and home servitude” – and to disregard repressive male authority by exploring their sexuality.

Profitable lobbying noticed the institution of refuges for girls and youngsters fleeing home violence and rape. In Australia, there have been groundbreaking political appointments, together with the world’s first Ladies’s Advisor to a nationwide authorities (Elizabeth Reid). In 1977, a Royal Fee on Human Relationships examined households, gender and sexuality.

Amid these developments, in 1975, Anne Summers revealed Damned Whores and God’s Police, a scathing historic critique of ladies’s therapy in patriarchal Australia.

Similtaneously they made advances, so-called girls’s libbers managed to anger earlier feminists with their distinctive claims to radicalism. Tireless campaigner Ruby Wealthy, who was president of the Australian Federation of Ladies Voters from 1945 to 1948, responded by declaring the one distinction was her era had referred to as their motion “justice for girls”, not “liberation”.

Like the primary wave, mainstream second-wave activism proved largely irrelevant to non-white girls, who confronted oppression on intersecting gendered and racialised grounds. African American feminists produced their very own important texts, together with bell hooks’ Ain’t I a Girl? Black Ladies and Feminism in 1981 and Audre Lorde’s Sister Outsider in 1984.

The third wave: from 1992

The third wave was introduced within the Nineties. The time period is popularly attributed to Rebecca Walker, daughter of African American feminist activist and author Alice Walker (writer of The Shade Purple).

Aged 22, Rebecca proclaimed in a 1992 Ms. journal article: “I’m not a post-feminism feminist. I’m the Third Wave.”

Third wavers didn’t suppose gender equality had been roughly achieved. However they did share post-feminists’ perception that their foremothers’ issues and calls for had been out of date. They argued girls’s experiences had been now formed by very totally different political, financial, technological and cultural circumstances.

The third wave has been described as “an individualised feminism that may not exist with out range, intercourse positivity and intersectionality”.

Intersectionality, coined in 1989 by African American authorized scholar Kimberlé Crenshaw, recognises that folks can expertise intersecting layers of oppression on account of race, gender, sexuality, class, ethnicity and extra. Crenshaw notes this was a “lived expertise” earlier than it was a time period.

In 2000, Aileen Moreton Robinson’s Talkin’ As much as the White Girl: Indigenous Ladies and Feminism expressed Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander girls’s frustration that white feminism didn’t adequately deal with the legacies of dispossession, violence, racism, and sexism.

Actually, the third wave accommodated kaleidoscopic views. Some students claimed it “grappled with fragmented pursuits and targets” – or micropolitics. These included ongoing points reminiscent of sexual harassment within the office and a shortage of ladies in positions of energy.

The third wave additionally gave beginning to the Riot Grrrl motion and “lady energy”. Feminist punk bands like Bikini Kill within the US, Pussy Riot in Russia and Australia’s Little Ugly Ladies sang about points like homophobia, sexual harassment, misogyny, racism, and feminine empowerment.

Riot Grrrl’s manifesto states “we’re offended at a society that tells us Woman = Dumb, Woman = Dangerous, Woman = Weak”. “Woman energy” was epitomised by Britain’s extra sugary, phenomenally well-liked Spice Ladies, who had been accused of peddling “‘diluted feminism’ to the plenty”. https://www.youtube.com/embed/tAbhaguKARw?wmode=clear&begin=0 Riot Grrrrl sang about points like homophobia, sexual harassment, misogyny and racism.

The fourth wave: 2013 to now

The fourth wave is epitomised by “digital or on-line feminism” which gained foreign money in about 2013. This period is marked by mass on-line mobilisation. The fourth wave era is related by way of new communication applied sciences in ways in which weren’t beforehand attainable.

On-line mobilisation has led to spectacular road demonstrations, together with the #metoo motion. #Metoo was first based by Black activist Tarana Burke in 2006, to help survivors of sexual abuse. The hashtag #metoo then went viral throughout the 2017 Harvey Weinstein sexual abuse scandal. It was used not less than 19 million occasions on Twitter (now X) alone.

In January 2017, the Ladies’s March protested the inauguration of the decidedly misogynistic Donald Trump as US president. Roughly 500,000 girls marched in Washington DC, with demonstrations held concurrently in 81 nations on all continents of the globe, even Antarctica.

In 2021, the Ladies’s March4Justice noticed some 110,000 girls rallying at greater than 200 occasions throughout Australian cities and cities, protesting office sexual harassment and violence in opposition to girls, following high-profile circumstances like that of Brittany Higgins, revealing sexual misconduct within the Australian homes of parliament.

Given the prevalence of on-line connection, it isn’t shocking fourth wave feminism has reached throughout geographic areas. The International Fund for Ladies studies that #metoo transcends nationwide borders. In China, it’s, amongst different issues, #米兔 (translated as “rice bunny”, pronounced as “mi tu”). In Nigeria, it’s #Sex4Grades. In Turkey, it’s #UykularınızKaçsın (“might you lose sleep”).

In an inversion of the standard narrative of the International North main the International South when it comes to feminist “progress”, Argentina’s “Inexperienced Wave” has seen it decriminalise abortion, as has Colombia. In the meantime, in 2022, the US Supreme Court docket overturned historic abortion laws.

Regardless of the nuances, the prevalence of such extremely seen gender protests have led some feminists, like Purple Chidgey, lecturer in Gender and Media at King’s Faculty London, to declare that feminism has reworked from “a grimy phrase and publicly deserted politics” to an ideology sporting “a brand new cool standing”.

The place to now?

How do we all know when to pronounce the following “wave”? (Spoiler alert: I’ve no reply.) Ought to we even proceed to make use of the time period “waves”?

The “wave” framework was first used to exhibit feminist continuity and solidarity. Nonetheless, whether or not interpreted as disconnected chunks of feminist exercise or related durations of feminist exercise and inactivity, represented by the crests and troughs of waves, some consider it encourages binary pondering that produces intergenerational antagonism.

Again in 1983, Australian author and second-wave feminist Dale Spender, who died final 12 months, confessed her concern that if every era of ladies didn’t know that they had sturdy histories of wrestle and achievement behind them, they’d labour below the phantasm they’d must develop feminism anew. Absolutely, this is able to be an awesome prospect.

What does this imply for “waves” in 2024 and past?

To construct vigorous sorts of feminism going ahead, we would reframe the “waves”. We have to let rising generations of feminists know they don’t seem to be residing in an remoted second, with the onerous job of beginning afresh. Fairly, they’ve the momentum created by generations upon generations of ladies to construct on.

Sharon Crozier-De Rosa, Professor, College of Wollongong

A REMINDER NOTE FROM THIS BLOG EDITOR:

I've republished this text from "The Dialog" below a Artistic Commons license.